WARNING: This is a rant against myself and maybe against you. Read at your own discretion. I will not be held responsible for any feelings of conviction that ensue.

Listen

Lord, that one little word keeps coming up again and again: listen.

I encountered it in Jeremiah today as for the umpteenth time, he obeys You and prophesies tragedy on Israel. You gave the Israelites the chance to repent so many times. You spelled out all the horror that would fall on them if they didn’t.

But the king would not listen.

As I’ve read books and tuned in to podcasts and soaked up a little of the frenzy going on in the US and the world, it seems the lament is simply this: Listen.

Let our brothers and sisters of color tell their stories without we white believers defending ourselves or sharing our trite and unhelpful two cents to the discussion.

Just listen.

I feel like this is especially what we evangelicals need to hear from You now.

Listen to our black brothers and sisters, yes! And listen to the thousands of gay Christians who are begging to be heard. Listen to their stories. Listen well, before we answer, “Sin! Sin! Sin!” Listen to their suffering even as we listen to the slave stories of old and of right now.

We think we know so well what the Bible says on these issues when so often Jesus was silent about such. Or rather, he didn’t explain things in a neat little tract about how to be saved.

I find Jesus hanging out with all the people we condemn. Oh, we say we aren’t condemning them. But instead of going to eat with gays and gals who have had abortions and militant blacks, we scream at them “Sinner! Sinner! Sinner! Come to church and let us fix you!”

I’ve said it for 30+ years, Lord. I feel like I’m standing in France and looking across the vast ocean to the huge island of America which is slowly sinking, sinking, sinking beneath the waters. I wonder if another Civil War is on the horizon?

And what breaks my heart is that evangelicals are often the culprits. We’re known for our hate not our love. We scream and protest and congeal together about one or two hot-button issues instead of going about our business of caring, loving one another, reaching out to the poor and marginalized not as a project to fix, but as an equally important human being to love.

I confess, Lord, that it feels like despair. And yet…

I see glimmers of hope all across the country and across my heart. I’m reading books by black authors and by millennials who have left the evangelical church over gender issues. I’m watching movies about slavery and injustice. I’m listening to podcasts about racial reconciliation as I cook dinner.

I am being stirred deep in my soul even as I stir my pot of soup.

Earlier in the chapter, the Lord has said, “Perhaps when the house of Judah hears about all the disaster I am planning to bring on them, each one of them will turn from his evil way. Then I will forgive their iniquity and their sin.”

But they did not listen.

I have a feeling that we as white evangelicals are still a lot like those Israelites of old. We are smug in our doctrine and cold in our hearts. We are screaming at the splinters in the eyes of all the sinners and absolutely refusing to look at the logs in our own eyes. Can’t we repent and beg You, Lord, to change us? Change me?

I just feel it in my bones, and I’ve seen it in my own life. When I really go about the business of confession and repentance and then I ask You what I am to do next, well, it becomes pretty clear. And it’s not to cast stones. It’s to smile across the hedge and, through simple acts of kindness, love my neighbor, really care about her, with all her indifference and rebellion.

It’s to listen with one ear attuned to my neighbor and one ear to You, dear Lord.

How can you listen today?

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog. + +

Here’s the link for the Facebook Live Video of the virtual tour. Enjoy!

People will say she is really just a tool shed, Lord. But You and I know differently. She has been my place to run to, my safe space, my ‘she shed’ a decade before there was even such a term. She’s much more than just my office. So I named her because naming her means she is seen. She’s my Writing Chalet.

When we moved into this house fifteen years ago, there were four small bedrooms: one for Paul and me, one for each of our sons, and one that would become Paul’s office. I need total silence when I write so somehow we’d have to find a place for me to work too. The house was perfect except for that one small problem.

So we bought it.

After we moved in, I noticed that the tool shed which sat on the front of the property, made of rustic planks with no flooring or insulation, had two windows that looked out onto the lovely front yard which the previous owners had filled with flowers and fruit trees and a pond. And the shed was cute. It looked like a miniature Swiss chalet with little wooden animals running across the front: a fox, a squirrel, a bunny, and a few birds in flight.

Right then, I began to dream of my new office, which I immediately dubbed my Writing Chalet.

It just so happened that Paul’s parents, affectionately known as Mamaw and Papaw, were coming for a visit. Papaw was the ultimate handyman with Paul a very able partner. And so they took my dream and made it come true. They laid flooring and put in insulation. Our sons pitched in to help with the project. Even our beloved mutt Beau was in on the job.

Soon after, I painted the walls a pale green and plastered them with photos. I installed old shelves and an ancient filing cabinet and a chest of drawers from Paul’s days in Brazil and the desk Paul had made for me years earlier.

And she became my beloved Writing Chalet. I delighted in walking the 35 steps from the front door of our home down to her front door with my laptop and a cup of tea. No phone, no food (well, maybe a square of dark chocolate tucked in my pocket), nothing but my desk, my laptop, my books and my photos as friends.

No matter how lovely I made her, she was at her core a tool shed, and my daily guests were daddy long legs and ants and other bugs that were, well, at times annoying. Still, I’d invaded the Chalet’s space, and she had welcomed me in, so I put up with these other friends the best I could. In winter I brought in a space heater to keep me warm. In the summer we installed a ceiling fan. The internet could be sketchy, but it usually worked.

My Writing Chalet became my sacred spot. She heard my tears of disappointment when I received a rejection and my prayers of praise when the writing was going well. She knew my joy when reading heartfelt letters from my fans.

She. Was. Perfect.

But fast forward fifteen years, and she desperately needed a redo. So last week, I dreamed of a new set up for her insides, and I dumped all my stuff in the front yard for four sun-filled days and nights. I scrubbed away dirt and swept away hidden spider webs. I repainted the walls and ceiling a clean, fresh white and stained the wooden shelves that Paul built.

As I write this post, I am sitting in my newly repainted, redesigned, and redecorated Writing Chalet. It’s been a ten day project, and I feel giddy with joy at my Chalet’s new look. Paul peeked in yesterday and said, “You’ve made it yours, now. You’ve finally expressed yourself in your way. Before you kind of just added stuff in and made do. But now, it looks like you.”

I am beyond delighted with the result.

I’ll be posting photos on Facebook and Instagram each day this week of The Writing Chalet Redo and next Tuesday I’ll take you on a tour via Facebook Live. Also, starting on Saturday, I’ll be running a 24-hour Giveaway for my novel The Swan House. This novel portrays systemic racism and one young woman’s awakening to white privilege.

So be on the lookout for photos and then please join in for the Giveaway. I know many of you, my faithful readers, have read The Swan House so if you win a copy, perhaps you could pass it along to someone else who needs encouragement for such a time as this.

I’m waving to you from my Writing Chalet with a heart filled with gratitude for the stories the Lord has allowed me to pen inside. And she, my Chalet, sends a bonjour too. She can’t wait to show you her new look!

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog. +

Lord, I have no words right now to explain the depth of my sorrow, anger, and despair. So I offer what I do have, words I wrote twenty years ago about a young white girl in 1962 whose eyes were being opened to racism. Oh, Lord, have mercy on us! Open our eyes again, and, with them wide open, show each of us how to move toward change.

*I borrowed the title ‘Waking Up White’ from Debby Irving’s excellent memoir, Waking Up White: and finding myself in the story of race. It should be required reading for all of us.

The following excerpt is from The Swan House, by Elizabeth Musser, c 2001

Chapter 4

There were several things that pulled me out of my depression at the end of June and during those early days of July: Trixie’s attention and Rachel’s constant phone calls insisting that we had to get a start on The Raven Dare. But it was especially Ella Mae who was determined to have her Mary Swan back.

“You is not much good to anyone, sugah, sittin’ round as you are, feelin’ sorry for yorese’f. Ya know what would do ya good?” Ella Mae said one day when she found me flopped across my bed, staring at a magazine.

“No idea,” I mumbled unenthusiastically. “Give me a hint.”

“You needs ta do somethin’ fo’ somebody else, Mary Swan. And I got jus’ the thing.”

I looked up from the magazine I was reading, the lack of interest evident in my eyes.

“You come downtown with me on Saturday mornin’. He’p out at Grant Park.”

I’d never been to the part of Atlanta called Grant Park, but I knew where it was—in the slums, in the inner city. “What do you mean by ‘help out,’ Ella Mae?”

“I mean you goes to he’p people who are in a heap o’ trouble and need a good hot meal and a listenin’ ear. That’s what I mean.”

“Who’ll be there?”

“Lotta blacks’ll be there. And some white folk, too, Swannee. It’s not the kind of thing you can explain too well. Ya have to see it for yorese’f.”

She didn’t twist my arm or anything, but somehow, Ella Mae convinced me to go with her to Grant Park, a part of Atlanta’s famous downtown that was now falling into disrepair. All the white families with money were moving out. I was petrified to tell Daddy where we were going, but when I did, he just said, “If Ella Mae’s taking care of you, that’s just great.” Anything that got his Swannee out the house seemed to have been fine with him.

Ella Mae took the bus to our house and arrived around ten-thirty that Saturday morning. I was still asleep. She backed the old blue Cadillac out of our two-car garage. Daddy had taught her how to drive it years ago, and she used it to take Jimmy and me to different outings. She was one of the few maids who could drive at that time, and she was proud of it and even prouder of her ‘Caddylac’, as she called it.

She honked once, and that got me out of bed. Five minutes later I rushed out of the house with a piece of toast hanging from my mouth. I hopped into the car, munching on the toast and gave Ella Mae a half-smile. We rolled the windows all the way down, and after I’d finished eating my piece of toast, I put my face to the wind and let the hot air blow over me. Riding with Ella Mae at the wheel was always a real adventure, the way she stomped on the brakes at a light and maneuvered the Cadillac along the streets. I decided I wasn’t as scared of getting into trouble in Grant Park as I was of getting into a wreck before we ever arrived.

She pulled up in front of a red brick church and got out.

“You didn’t tell me I was going to church,” I complained.

“And you didn’t ask.”

So I spent a good bit of Saturday morning and afternoon with Ella Mae in a big room in the basement of Mount Carmel Church. Paint was peeling off the walls, except for where a mural had been painted near the side door, and a lot of long metal tables and folding metal chairs were arranged on the left side of the room.

“This is our fellowship hall, where we has our meals and such,” Ella Mae explained. Then she led me into the adjoining kitchen to meet a white woman named Miss Abigail, whom Ella Mae called ‘an angel in the devil’s boilin’ pot’. According to Ella Mae, Miss Abigail had moved to Atlanta in the mid-fifties from Detroit where she’d worked in the slums for sixteen years. Miss Abigail looked like she was older than Daddy and younger than Ella Mae which would have made her around fifty. Her hair was mostly black and thick with streaks of gray here and there and she wore it long and pulled back in a ponytail, which struck me as odd for a woman of her age. But what I really noticed about her were her eyes. To this day I can never remember their color. I think they were just a very ordinary brown. But that day, as on most every other day I was with her, Miss Abigail’s eyes sparkled. There’s no other word for it. They sparkled like she’d just been told she had won a million bucks.

She was of medium build and she wasn’t very tall, several inches shorter than me, and I was five feet five, but, according to Ella Mae, she was tough. She had spent her life on the streets, serving the poor and homeless, one of the first white women to do such a thing in Atlanta. And Ella Mae decided that it was time for me, a spoiled, rich kid who was feeling sorry for myself, to see how another part of Atlanta society lived.

Miss Abigail was leaning over a big aluminum sink, washing lettuce leaves. She turned around to greet me, wiping her roughened hands on the faded green apron she wore. Then she extended her hand. “Thank you so much for coming down to help us today, Mary Swan.” Miss Abigail’s voice carried no hint of the Southern drawl we knew in Atlanta. I gave her a half smile and a shrug.

She didn’t seem to notice. “There are over four hundred and fifty families living in Grant Park and most of them are desperately poor. A large percentage of the kids have never known their fathers and are being raised by their grandmothers. About a year and a half ago, we started offering spaghetti lunch once a week to any who wanted it. Volunteers from both white and black churches take turns preparing and serving the food. Ella Mae is one of the most faithful.” She stated the facts coolly. “You can help out with serving the sauce.” She pointed out from the kitchen into the big room adjoining it. Steaming pots of spaghetti sauce and bowls of noodles were sitting on two long tables which separated the workers from the assortment of people milling around the room, waiting for lunch.

The spaghetti was overcooked and stuck together, the plates cracked, and the pots and pans dented and stained. Ella Mae said that all the silverware had been stolen the week before so that she and Miss Abigail had to go down the street begging the neighbors to borrow forks and knives at the last minute. I stood there, awkwardly holding a ladle in one hand, waiting for them to return. The people standing in line were mostly sad-looking men, in thin shirts and greasy pants that hung on them, or heavy-set women with thinning hair, or teenage girls with one or two little children in tow. And there were a mixture of whites, blacks and Mexicans.

I found myself serving spaghetti that Saturday beside a boy who was about eighteen or nineteen, strong-looking and tall, over six feet, and black as the Ace of spades, as Granddad would say.

“Hello. I’m Carl,” he said, staring down at me with the ladle of spaghetti sauce in my left hand. “Hi. My name’s Mary Swan.” My voice sounded a little strained, and I bet my face was crimson.

“Nice to see ya here, Mary Swan.” His smile was wide and white.

“Nice to be here.” I tried to smile and then I cleared my throat. “Do you come here a lot, Carl?”

“Most weeks I come. Helping Miss Abigail.”

“Why do you want to help her?”

He smiled again. “’Cause she’s the one who helped me get back in school. She helped me find an afternoon job so that I can make some money for my family and still go to school. She’s one fine lady.”

And that was how I formally met Carl Matthews.

I couldn’t think of anything to say, which, as my friends often commented, was rarer than an uncooked piece of beef. It was just that it seemed more like I was in Africa or Haiti than in Atlanta. I’d lived here all my life, but I didn’t know a thing about this side of the city.

“You have any brothers and sisters?” I ventured.

“Yep. Three of ‘em. I live with my two younger brothers, my little sister and my aunt.”

“What about your parents?”

“My mama’s dead. She died when I was twelve.”

That made my heart skip a beat. “Was she sick?”

“Got shot. Big fight between her and her boyfriend. You know what I mean?”

I didn’t have the faintest idea, and it sounded absolutely gruesome. “What about your dad?”

Carl’s smile was cynical. “I’ve never met my dad. Don’t know him from Adam.” He chuckled, and I wondered if there was bitterness behind those black eyes.

“My mom’s dead, too,” I offered, feeling worse by the minute.

He shrugged, not a bit curious like I was. Maybe in his part of Atlanta it was the most common thing in the world to be an orphan. To never know your father and to have your mama killed in an angry dispute, leaving four kids to fend for themselves.

Finally, after he’d slopped spaghetti sauce on several plates and murmured “The Lord bless you,” to several men, he asked, “How’d she die?”

“In the plane crash in June. Did you hear about it?”

“Yeah, I know about that, Mary Swan.” He looked almost offended. “I read the papers, too. I don’t reckon there’s a soul in Atlanta who didn’t shed tears over that tragedy. Didn’t know anybody on that plane. But it broke my heart. A whole lotta pain in Atlanta.” Then he met my eyes, and I saw kindness and sorrow in his. “I sure am sorry for you, Mary Swan.” And I knew, with a tingling down my spine, that he meant it.

But I didn’t want to talk about the plane crash. After all, I was coming down to the inner city to get away from my problems and listen to someone else’s. So I went back to asking about Carl’s family. “So your aunt took care of you after your mom was killed?”

“No. My aunt was in no shape to care for us. It was Miss Abigail. Good thing she arrived in Atlanta ‘bout that time. She took us in and fed us and got us to school and loved on us just as if she was as black as we were.”

“But you’re living with your aunt, now?”

“That’s right. Took us awhile to get things back together, but we’re coming along.”

“And you go to school and then work in the afternoons?” I didn’t know any teenager in Buckhead who had a job after school.

“Yep. I missed two years of school ‘cause I had to be working. To help pay the bills. Ya know what I mean? Like I said, Miss Abigail got me the job in the late afternoon so that I could go back to school. She says I’ll be able to go to college one day if I want to. And I do.”

I was glad that we ran out of spaghetti just then so that when I went into the kitchen Carl thought it was just to get another pot of noodles. But really, I was crying, crying for this kind boy who told his tragic tale as if it were the most natural thing on earth. And it struck me then, that in his world, this world of the inner city of Atlanta, maybe it was.

The next Saturday morning I was up and dressed and waiting almost impatiently for Ella Mae to drive up. Daddy didn’t say a word about it. He just watched me go with this mixture of pain and relief in his dark brown eyes. I think that anything that got me out of the house that sticky July was considered by my daddy to be a small miracle.

And Ella Mae was right. It did seem to help to leave Buckhead and its grief for a few hours and discover another type of pain in Grant Park. But mostly I think I agreed to go back because something deep and rebellious in me wanted to be friends with Carl. I’d never had a black friend my own age. Blacks weren’t allowed at Wellington. Only one school district in Atlanta was desegregated and it wasn’t mine.

After the meal was served, Carl shooed Miss Abigail out of the kitchen. “You’ve got people to be talking to, now. Go on. I’ll clean up.” I noticed right away how protective he was of Miss Abigail. And I noticed something else. He knew how to clean up. The prospect of having his elbows in that sudsy water as he washed plates and silverware and pots and pans didn’t seem to bother him a bit. “Wanna help?” he asked, smiling that same wide, white smile.

“Sure,” I shrugged.

“You wanna wash or dry?” He was already rolling up his sleeves. “Doesn’t make any difference to me.”

I was petrified. I had no idea what to do; I’d never washed a dish. But I was also proud. “I’ll be glad to wash.”

He had lined up all the pots and pans and plates and glasses and silverware on one side of the sink and put a stopper in the sink. The hot water bubbled into a foam when he squirted a little of the dishwashing liquid into it. I looked at the pile of dishes beside me and grabbed the biggest pan, caked with red sauce. Plunging it into the sudsy water, I stifled a little howl of pain. That water was hot! With a soggy sponge, I started scrubbing the pan with its stubborn sauce. The water was turning a dull shade of red, and I felt the sweat prickling my brow and upper lip. The pot would not come clean.

It took a moment for me to realize that Carl was staring at me with that same smile on his face. Then he scratched his head as if he were perplexed. “I’ve never seen anyone do dishes like that before. We always start with the glasses and silverware and save the pots and pans ‘til last. Let ‘em soak in the water. Ya know what I mean?”

My cheeks were burning, and I was inwardly cursing this boy who had the nerve to tell me how to wash dishes! My mind searched for a reply that would put him in his place. But before I could say a thing, he took up the rag and said, “Here, I’ll show you, Mary Swan. I don’t guess you’ve had the chance to do many dishes with Ella Mae there all the time.”

He wasn’t snooty or bitter or self-righteous. It was a statement. But it still bugged me to death, the way he smiled so politely and then changed the water and started all over. I felt like he had slapped my hands for committing a terrible sin. Humiliated, I grabbed a dishtowel and started drying the glasses he placed in the dark green dish holder.

Somewhere between the silverware and the last pan, I got over my humiliation. When all the dishes were dried and stacked, we walked into the big room where Miss Abigail and Ella Mae were engrossed in a conversation with a sickly looking white-haired woman.

“Leave ‘em be,” Carl whispered to me. “They’re always talkin’ and prayin’ with people. Wanna go outside? I’ll take you to my house.”

I shrugged, thinking I should at least tell Ella Mae what I was up to. When I did, she got a scowl on her face and said, “Fine little jaunt ova’ ta yore house, Carl. Gonna take ya awhile.”

“We’ll be careful, Ella Mae,” Carl said solemnly.

Miss Abigail nodded at Ella Mae and smiled at Carl, so Ella Mae just shrugged and said, “Y’all be back fo’ too long.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Carl said. And to me, “You can meet my brothers and sister.”

It was hot and miserably muggy outside as we walked down the street. Carl pointed at a massive old Victorian house with trash in the yard and windows broken out. “Twelve different families live in there.”

“In one house?”

“Yep. White families. That there’s a tenement house. Lots of ‘em ‘round these parts.”

Many of the houses were two story and Victorian-looking. Some, I could tell, had been beautiful old homes. But now, virtually all were in disrepair. “Whites and blacks live in this neighborhood?”

“Yep. Used ta be only rich white folks. Then they got scared and run lickity split away from here, so that’s when the poor whites moved in. Now ya got both blacks and whites and Mexicans, too, but they don’t like mixin’ together. ‘Cept at the church, when there’s a free meal offered,” he said, chuckling a little. “Ova’ where I live near Cabbagetown, it’s all black families.”

“Cabbagetown! That’s really what it’s called?”

He smiled. “Sure is. This here’s Grant Park, and then there’s Cabbagetown. And not far away there’s Mechanicsville and Buttermilk Bottom and Summerville and Reynoldstown. Those are all black neighborhoods.”

“Funny names, but then again, I live in a place called Buckhead.”

“Buckhead. Yeah, I’ve heard of Buckhead. Lotsa ladies I know work in Buckhead.”

“You know where the name came from?”

“Nope.”

“Well, the story goes, that back in the 1800’s, a man named Henry Irby shot a large buck near Paces Ferry Road and Peachtree.” Peachtree was a wide road that ran smack through Atlanta from South to North. “Then he mounted the head on a post in front of his tavern and people started calling the place ‘Buck’s Head’.”

Carl grinned, “Makes sense.”

“And do you know where the name Peachtree comes from?”

“Now, Mary Swan, that ain’t too hard. Comes from a peach tree, I reckon. Musta been a lotta them round these parts, the way they call everything in this city Peachtree somethin’.”

“Well, might be because of the peach trees and it might be because of the pitch—you know, the resin, in pine trees.”

“You mean it shoulda been called Pitchtree?” He narrowed his eyes in a teasing way.

“Yeah, maybe. Fact is, there weren’t that many peach trees around back in Indian times. But one thing’s for sure. Indians lived here, Muscogees and Cherokees and there was a village known as Standing Peach Tree right where the Chattahoochee River meets Peachtree Creek.”

Carl lifted his eyebrows. “They teach you stuff like that at your school?”

“No, I read it in a book.”

“Well, that’s just fine.” He stopped then and said, “That’s where I work in the afternoons,” indicating a gas station with a sign that read Abe’s Fill ’er Up. “I don’t know who named the place, but I figure it pretty well explains what it’s here for.” He was grinning from ear to ear. I almost stuck my tongue out at him, but by now, I knew his teasing was perfectly harmless. “And over there’s the Rite Price Laundromat where me and my friends hang out on the weekends.”

We must have been walking for at least fifteen minutes, and I was beginning to wonder if I should have come with him. “Are we almost there?”

“Not far now, Mary Swan. Over there’s the cemetery—they call it Oakland. Right famous place,” he commented.

Oakland Cemetery! Way across the street, I could see a tall red brick gateway rising in three arches with wrought iron gates marking the entrance to the cemetery. Carved in the stone above the main arch was the word Oakland.

I nodded in the direction of the cemetery and said, “That’s where my mom is going to be buried.”

“Go on. Ya don’t mean it?”

“Sure I do.”

“She hasn’t been buried yet?”

“No. Daddy and the rest of the people who lost family members in the crash are dealing with lots of red tape in getting the bodies back to the States. Most of the funerals are just now taking place. Mama’s is scheduled for next Saturday.” I suddenly felt a funny catch in my throat.

He walked with me to the entrance to Oakland and I peeked through the gate. Tall oak and magnolias lined a narrow red brick cobbled road with stone monuments on each side. “Have you ever been inside, Carl?”

“Yep. Lots a times. Big ole place, sprawlin’ out all over. Kinda run down now. But mighty lot of famous folks are buried in there.” He got this distraught look on his face, just for a second, and then he turned away from the cemetery and kept sauntering down the street. I watched him take his long, nonchalant strides.

I wondered if he liked to wander around in cemeteries or if he went in there to attend funerals of people he knew. I found it hard to swallow. My head felt light and I wanted to sit down on the curb, but Carl was already halfway down the street. I felt an awful aching inside for my dead mother, but even more so for this boy who was an orphan, who attended a run-down church and had a night job and had missed two years of school so he could help care for his siblings. I had to jog to catch up with him, and when I did, I was sweating and out of breath from the thick heat. “It must be really hard to be a Negro,” I said softly. Then I wished I hadn’t.

He looked over at me, wrinkled his brow and shrugged. “I’m used to it.”

We walked a little further without saying a word. The houses on this street were small, wood clapboard, different colors, many with peeling paint. Many had little porches on the front, and on some of those porches, a man or a woman sat rocking back and forth and fanning himself. And staring at me as if I were a Martian. And I guess I stared back, all the while thinking to myself This is what poverty looks like.

It wasn’t so much the unkempt homes or the sparse grass and trash along our route. It was the people. The children with a kind of dirtiness that meant they hadn’t taken a bath for weeks. The men with toothless smiles and the wide women wearing clothes that looked like they’d picked them out of a rummage sale with their eyes closed. It was something I couldn’t quite define—something that made me feel sad.

“Here’s where I live,” Carl said. He stopped in front of a white wooden house. Its yard was neat with potted flowers on the front porch. I couldn’t help but notice the contrast with several of the surrounding homes which had car carcasses in the front yard.

As soon as he opened the screen door, his siblings came to greet us, one of the boys calling out, “Carl’s here. He done brought a friend. A white girl!” The two boys studied me solemnly at first. The little girl, who couldn’t have been more than seven or eight, stood beside Carl and gave me a shy smile.

“Mary Swan, I’d like ya to meet my little brothers, Mike and James and my sista, Puddin.’”

Mike, the oldest, stepped forward and held out his hand “Pleased ta meetcha.” He puffed out his chest and mashed my hand in his, so that I stepped back and said “Ouch!”

“Mike, watch yo’se’f, boy!” Carl remonstrated in a voice that was very different from the one he used when he talked to me. Then he said, “Excuse us, Mary Swan. He’s mighty full of himself for a twelve-year-old, but he’s all right.”

“Nice to meet you, Mike,” I said. “Good grip you’ve got there.”

Immediately the other boy rushed over to shake my hand. “I’m James and I’m ten.”

I regarded him warily with a sliver of a smile on my lips, “Good to meet you, too. Be careful with my hand, please.”

He opened his mouth in a smile, took my hand and pumped it up and down several times. I pulled my hand away and shook it down by my side, pretending to be in pain. The boys stared at me silently. Then I winked at them and they burst into laughter.

The little girl gazed at me timidly. “I’m Puddin’, and I ain’t never heard a name like Mary Swan before!”

I bent down to her level and shrugged. “I know. It’s kinda weird. Family name.”

Their eyes got wide at that comment, and James said, “You mean they’s lotsa folks in yore family called Swan?”

I laughed, “No. That’s not what I meant.”

But Carl brushed it aside and said, “Why don’t y’all take Mary Swan to the kitchen and we’ll fix her some iced tea?”

Puddin’ took my hand in hers and said, “Come on in our front room.” We left the porch and went through this “front room” which looked to me just like a bedroom. A table in the corner was piled with newspapers and old magazines, the floor had a dirty rug and a dirtier dog on it, and a skinny woman with droopy eyes that followed my every move sat on an unmade bed.

“Afternoon, ma’am,” she said with a scowl on her face.

“Good afternoon,” I replied and licked my dry lips.

“That’s my Aunt Neta,” Puddin’ confided as she led me through the front room and into the kitchen. Mike opened the fridge, and James gave me a big grin and pointed to a chair. I sat down and tried my hardest not to stare at the flies that were swarming around several crusty plates that sat beside the sink. I could hear Carl whispering something unintelligible to his aunt.

Mike placed a glass of iced tea on the table and Puddin’ whined, “I want some, too, Michael. You betta fix me some right now.” Then she stood behind me and started twisting my hair around her fingers.

James gave her a hard look and said, “Stop it, Puddin’! Ain’t polite.”

“Oh, no. It’s fine,” I said and winked at Puddin’. “Do you think you could braid it for me one day?”

Puddin’ scrunched up her nose, looking very unconvinced. Then she giggled. “I could try, I guess. Shore feels funny, yore hair, Mary Swan. All thin and straight.” She giggled again.

For some reason, I pulled her into my lap and started tickling her, like I used to do when Lucy was younger. Puddin’ howled with delight, and Carl came into the kitchen to see what was going on. When he saw Puddin’ squirming happily on my lap, he nodded at me in approval.

So I stayed at Carl’s house for about an hour and listened to the kids babbling about their dog and their friends and their school, and I forgot all about Buckhead and Mama and Oakland Cemetery. And when Carl said we needed to be getting back to the church so that Ella Mae wouldn’t worry, I didn’t really want to leave. I felt all warm inside and nervous, like when I’d been given The Raven Dare. Only this seemed so much better. I’d discovered a whole new world.

Chapter 5

It was on July 14 that we buried Mama. Daddy chose that day because Mama, being half French, loved France, and that was France’s Independence Day. The funeral services for the victims of the crash stretched over the whole summer, and I went to probably fifteen of them along with Daddy and Trixie and about every one else in Buckhead. And Mama’s service at St. Philip’s was filled with the same sad people wearing their black suits and dresses, dabbing their eyes with handkerchiefs as they quietly cried.

Daddy’s family had several plots in Oakland Cemetery. It was an historic place because it was the first cemetery in Atlanta, established in 1850. The first twenty-five of Atlanta’s mayors were buried there along with the great golfer Bobby Jones, the author of Gone With The Wind, Margaret Mitchell, a lot of Confederate soldiers and a large portion of Atlanta’s elite families, white, black and Jewish. But, as I’d seen with Carl, it was located in the section of Atlanta that was fast becoming known as the bad part of town. As we drove to the cemetery, I thought of my peek through the bars last Saturday. For a split second, I forgot I was at Mama’s funeral and remembered the afternoon with Carl and his family. It was a pleasure to lose myself for a moment because I felt like I was suffocating inside. We’d cried and grieved and hurt and now we had to do it all over again. Would Atlanta never finish grieving for her dead?

A bunch of my friends were there and some of Jimmy’s. After the graveside service, Jimmy wandered over to stand with his friend Andy Bartholomew. Andy’s older brother, Robbie, was my age, and I’d met him several times before. Now he came up to me. He reminded me of a cross between a football jock and a Boy Scout—and actually, he was involved in both of those activities. He was as tall as Daddy, maybe six feet, with reddish blond hair that was cropped short and a tanned face and warm golden eyes. He had an athletic build, strong and svelte, but when he smiled, his face filled with dimples and he lost any suave look and seemed, I don’t know. He seemed nice, kind. Boy Scoutish.

“I just wanted you to know again how sorry I am, Mary Swan,” he said, clearing his throat. He managed a half-smile and one dimple appeared. “You know my family’s here if there’s anything we can do.”

“Thanks, Robbie.” I felt suddenly awkward in my new black linen suit from J.P. Allen’s and nibbled on my lip. “You know, Andy’s been great about inviting Jimmy over. It’s no fun being alone with your thoughts in our big house.”

“Andy’s glad to have Jimmy over.” He reached for my hand and held it briefly. “I am so sorry, Mary Swan.” He started to leave, then added, “And if you need anything, if you ever want to get a burger or something, there’s a bunch of us who meet at the Varsity on Sunday evenings.” He smiled briefly again and met my eyes.

I could feel the heat running up my cheeks. “Thanks. Thanks, Robbie. I’ll think about it. I will.”

As soon as Robbie walked away, Rachel Abrams was by my side, poking me in the ribs. “Talking to Robbie Bartholomew, are you?” she teased.

“Rachel! Don’t you have any respect for etiquette!” I scolded. “It’s Mama’s funeral.”

Rachel gave me a quick hug and then took me by the shoulders. “I loved your mom, and I love you. And you know as well as I do that life has got to keep going. It can crawl by unnoticed while you suffocate at home or it can be discovered.” Then those magnificent blue-gray eyes of hers gleamed at me as she whispered mischievously, “And who are you to talk to me about etiquette anyway?”

I wiped the frown off my face and confided. “He offered, well kind of offered, to ask me to the Varsity. I mean he said I could come.” I almost giggled.

Rachel glanced around and then pulled me away from the main crowd of people around the grave sight. Her eyes were on fire. “Well, tell me more!”

I wiped my perspiring brow. “Not here, Rach. I have to see all these people. But come over tonight. And I’ll tell you about it. And about something else…”

“What else?”

“Someone I met,” I answered ambiguously.

“Tell me now!”

“Tonight!” She would have pulled it out of me if I hadn’t seen out of the corner of my eye Helen Goodman, this flirtatious woman who had quite a reputation, deep in conversation with Daddy. Something inside me bristled, and I whispered, “I gotta go, Rachel. See you tonight.”

It started to rain a little. Everyone stood there respectfully, talking in low tones, in spite of a steady drizzle and the thunder in the background. It seemed fitting for Mama to be buried in the rain. She had died on a perfect summer day in Paris. But I didn’t mind her being buried in the rain.

Late that afternoon after the funeral, I found Daddy in his study, his desk crowded with neat piles of papers, his head in his hands. I knocked softly on the opened door.

“Can I come in, Daddy?”

He looked up, gave me a weak smile and nodded. “Sure, Swannee. What’s up?”

“Are you okay, Daddy?”

“It was a hard day.”

“Yep. Really hard.”

He motioned for me to come to him, and scooted his big leather chair back away from the desk, so I could perch on one of the arms. “What are you doing?”

“Looking over papers for the Museum. And for my clients. Lots of legal problems with the crash, Swannee. Lots of money floating around.”

“And you’re in charge?”

He shrugged, “Yes, of quite a few of the estates. It’s good for me to be busy.”

“Are they gonna make that memorial arts school in honor of the victims of the crash? Has a lot of money come in?”

“Yes, quite a lot, but it’s a bit complicated, Swannee.”

“You can tell me about it if you want.”

“That’s just what your mama would say. ‘JJ, don’t look so worried. Tell me about it.’ But,” he smiled sadly, remembering something, “Mama couldn’t handle business talk for too long. Pretty soon her eyes would kind of glaze over and I could tell she was far away thinking of a painting. Bless her soul.”

“I’ll listen, Daddy. I promise.”

Daddy sat back in his chair and stretched his long legs out under the desk. “A lot of people think Atlanta is just a small southern city with not much to offer, kind of backward. But many Atlantans, and plenty of them who died in the crash, felt differently. They wanted, we want, Atlanta to be a cultural center in the South. We have a long way to go. You know what Symphony Hall looks like.”

I nodded. The Atlanta Symphony played in the Municipal Auditorim, a shabby building that was built in the early 1900’s and was now only fit, as Mama used to say, to house cock fights and circuses.

“If we want our city to keep up with the likes of New York and Washington, we need a reputable arts center that fuses visual arts, performing arts and art education into a single institution.”

“You mean a place for the symphony and the theater?”

“Exactly. As well as an art museum and an art school.” He chewed on a pencil. “So for a while we’d been trying to set up a big fund raiser to launch the project. Then came the crash and gifts started pouring in to the Art Association. So we’ve got to decide what to do with that money, and the consensus is to use it to start a new arts school.” He placed a hand lightly on my back. “You know what people are saying, Mary Swan?”

I shook my head.

“They’re saying that arts in Atlanta will rise again, from the ashes of the plane crash, just like the city itself rose from the ashes of the Civil War.”

“The phoenix, right?” I knew well that Atlanta’s symbol was the beautiful mythological bird which was fabled to live 500 years in the Arabian wilderness, burn itself on a funeral pyre and then rise from its own ashes into youth, to live in an unending cycle.

Daddy nodded. “The phoenix.”

“Did lots of the crash victims leave money in their wills to help with the museum?”

“As a matter of fact, that’s just what I’m working on. Look at this.” He found a neat pile on his desk and pulled out a folder. Weinstein was marked across the top. “Remember Mr. and Mrs. Weinstein? They both died on the plane. And two days before the crash, Mr. Weinstein and I had been talking about the Art Museum’s potential fund raiser while we sat in that famous café, Aux Deux Magots, on the Left Bank in Paris. He said he had some money to give and that he’d show me what he was thinking when we got home. But he never got home. And I’m in charge of the estate and have to prove that the money is there for the Museum.”

“You can’t get away from the crash, can you, Daddy?”

“No. No, sure can’t. Not for a long time. A real long time.” He turned towards the big picture window that looked out onto the carport. “They’re setting up a memorial exhibition at the museum for the artists who perished in the crash. Two of Mama’s paintings will be displayed.”

“Really? When will it open?”

“Very soon, sweetie.”

“And have you picked which paintings to show?”

“Yes, though it wasn’t easy to decide. There are so many more to choose from than I would have thought.”

“What do you mean, Daddy?” We both knew that Mama had never been considered a prolific painter. “Have you found more of her paintings?”

He had that far-off look in his eyes. “What? More paintings. No, no. Of course not, Mary Swan. Where would we find more paintings?” But the way he said it made me feel really funny inside.

“So which ones did you choose?”

“I figured we had to send one of The Swan House. Absolutely. And I wondered, I wondered if you’d mind if I lent the museum the painting of you on the tree swing?”

“Honest, Daddy? You want them to display that one?”

“Only if you don’t mind.” He started making excuses, misreading my thoughts. “Hard to part with it, even for a couple of months. Leave an awful kind of emptiness in the entrance hall, I guess. Maybe that’s not such a good idea.”

“Oh, no, Daddy! I don’t mind. It would be…” I got a lump in my throat. “It would be an honor for me.”

“Good then. We agree.” He rested his hand on my back. “I’ve set up a special fund for donations that have come in specifically in memory of your mother, too. What do you think she’d want those donations to go towards?”

“Something about art, for sure,” I said without hesitating.

“Exactly what I thought. I’m calling it the Sheila McKenzie Middleton Memorial Fund, and I’ve stipulated that it is to be a scholarship fund to help struggling artists get the training they need.” The more Daddy spoke, the more his voice kind of quivered.

“It sounds good, Daddy. Really good.”

“Yes, I thought it was the right thing to do.”

I kissed him on his cheek, wishing it weren’t so gaunt and prickly. Wishing that Daddy would sit up tall at his desk and talk loudly on the phone and then push his big leather chair with the brass studs on the sides back and go to the closet and pull out his golf putter. That’s what he always used to do. Play golf in his office.

But he hadn’t held that golf club since the crash, and from the look on his face, I didn’t know if he ever would again.

Rachel rang our bell at seven that night. She had her drivers’ license and her parents let her drive at night if she wasn’t going too far. It didn’t take her more than two or three minutes to drive from her Tudor-style house on the corner of Andrews and Cherokee to mine. She walked straight through the entrance hall and into the breakfast room where she plopped down at the big round oak table. “Tell all,” she demanded. She was curled up in the chair, her thick blond hair falling on the table as she leaned on her hands.

“You want some ice cream?” I asked nonchalantly.

“Swan, quit stalling. Out with it!”

“Do you want some ice cream?” I repeated. “I’m dying for some. We just got some chocolate chip at the store.” I opened the freezer and removed the carton.

She rolled her eyes at me. “Fine. Sure. So what’s up?”

I took two bowls down from the bright yellow cupboards, the ones Mama had painted with different fruits on each door. This door was covered in cherries.

“I’ve met someone interesting,” I stated as I piled the bowls high with scoops of chocolate chip ice cream.

“More interesting than Robbie Bartholomew?”

“Very different.”

“Okay, so? Where’d you met him?”

“At church.”

“Right. Come on, Swan. ‘Fess up.”

“It’s true. I met him at church. He’s nineteen and…and you may get to meet him sometime.”

“Impossible. Remember, I’m Jewish. I don’t go to church.”

“No, not at church. You might meet him someday at Oakland Cemetery. He goes there a lot.”

She rolled her eyes again and took a big bite of ice cream. “You’re nuts.”

“He lives right down the street from the cemetery.”

I let that sink in. She set down her spoon, narrowed her eyes and said, “You met him at church, and he lives near Oakland Cemetery. Hold on a minute. Do you mean that he’s black?”

“Yep. Name’s Carl.”

Rachel had uncurled and leaned across the table, grabbing my hand. “This is not talk for the kitchen. Come on!” She pulled me up from my chair, leaving our bowls half-filled with melting ice cream there on the table. We dashed through the hall, up the stairs until we reached the third floor and fell, laughing and panting, on my bed.

For a moment, every thought of Mama was gone. I reveled in my story. Rachel was as much of a rebel as I, and this ranked right up with the last poem I’d transformed in Mrs. Alexander’s class. So I told her about Mt. Carmel Church and Miss Abigail and serving spaghetti with Carl and not knowing how to wash dishes. We giggled until our sides hurt. And then I told her about visiting Carl’s house and his siblings and how his mother died and anything else I could remember, and I had the satisfaction of seeing her eyes grow bigger with each fact I related.

Finally she asked, “Do you like him, Swannee? Is that what you’re telling me?”

“Yeah, I like him. We’re gonna be friends. I guarantee it.”

“What do you mean by ‘friends’?”

“Oh, that you’ll just have to wait and see.”

We talked long into the evening, stretched out across my bed, the windows wide open and the faintest breeze ruffling the curtains. And I didn’t consider once what I meant by the fact that Carl and I were going to be friends. But it wouldn’t take me long to find out.

I could hardly wait for the next Saturday to roll around. The prospect of seeing Carl, and maybe Puddin’ and Mike and James, and of visiting Mama’s grave filled me with some sort of adrenaline. I thought about it the whole week, and how much I wanted Rachel to meet Carl, and then I had a crazy idea. I decided I would ask Carl to be my second assistant with The Raven Dare.

Way back in June, I had made up my mind that I couldn’t ask Daddy or Ella Mae to help me. Daddy would never have approved of me digging around in the past, and every time I mentioned anything about Mama, Ella Mae’s eyes started shining with tears. Daddy and Ella Mae would have the surprise of their lives when they attended the Mardi Gras celebration and found out that I was The Raven and that I had solved the dare. It was maybe a bit presumptuous of me to think like that, but it gave me the courage I needed to face each day. That became more important as the days slipped away and the new school year approached. It would be my secret, and I would solve that dare and bring Mama’s lost painting back to the High Museum even if it killed me.

So that next Saturday at Mt. Carmel, standing next to Carl, I could not contain myself. He listened and at least acted interested as I explained The Raven tradition at Wellington and how I’d been chosen and about finding the clue at midnight with Rachel.

He made a face. “Sounds awful silly to me, Mary Swan.”

“But it could be important for the school and the Museum.”

“If you say so, Mary Swan.” He swatted at a fly that was hovering over the spaghetti sauce.

“Haven’t you ever heard about the paintings that disappeared right before they were to be donated to the Atlanta Art Museum?”

“Nope, I’ve never been to no art museum. Never heard nothin’ about it.”

“You’d like the Museum. I know you would. Two of Mama’s paintings are going to be on display there. Another one should be, but it just disappeared. That’s what the dare’s about.”

“Two of your mama’s paintings are there, you say?”

“Yeah—they will be soon.”

He whistled low and smiled. “They let black folks into that museum?”

“Of course!” I said indignantly, but really I had no idea. I couldn’t recall ever having seen anyone black there except for Ella Mae when she went down with Mama and me.

“All right, then, Mary Swan Middleton. I’ll go with you to that museum and I’ll help you with that silly dare, if ya want.” He poked out his lower lip, shook his head, slopped some sauce on a plate and said, “My, my. If that don’t beat all.”

“But you’ve gotta swear you won’t breathe a word about it to anyone, Carl.”

“Gee, Mary Swan. Who in the world am I gonna tell about a big black bird?” His eyes twinkled.

“I don’t know. But you can’t tell Miss Abigail and certainly not Ella Mae. Or anyone. If you do, I’ll be disqualified. Do you swear?”

“Ain’t good to swear, Mary Swan.” I started to protest, but he laughed and assured me, “I won’t tell a soul. Not a soul.”

I wiped my hands on my apron when the last plate had been served. Today I was ready to wash the dishes with Carl. I started with the glasses and felt rather proud when I’d washed the last pan and only changed the dishwater once. As I was taking off my apron, I caught sight of Ella Mae in the big room and called out to her, “I’m going down to Oakland Cemetery.”

Ella Mae frowned, put her hands on her ample hips and shook her head. “No ma’am. You cain’t be a goin’ over there by yoreself, Swannee. It ain’t safe.”

Miss Abigail came into the kitchen, wilted tendrils of her hair sticking to her face. She ran her hand across her perspiring forehead and shook her head, with a wry smile. “The Lord’s provided again, just the right amount, praise His name. We’ve only got a spoonful of sauce and half a pot of noodles left. And we just ran out of bread and brownies and iced tea. Everyone’s been fed plenty.” She held up the half-filled ladle of sauce as evidence. She liked to remind us of “God’s provisions”, as she called them, how God always provided just enough, and the way she talked, you did kind of get caught up in her enthusiasm. She joined Ella Mae and before long, both women were sitting in those folding chairs talking to other women, the women Ella Mae had described as having a “heap o’ troubles.”

“I’ll take ya to the cemetery, Mary Swan.” Carl was drying his big hands on a wet dishrag and then wiping it across his shining face.

“You don’t mind?”

“’Course not. Go on.”

So I ran over and told Ella Mae who wrinkled her brow and admonished me to be careful. Carl left the dishtowel on the back of a metal folding chair, and I followed him out the basement door of the church, squinting as the sun struck me hard in the face. The walk took us at least ten minutes and we didn’t say much, I don’t think. But when we got to the opened gates, he said, “This cemetery is divided into different parts for the whites, the blacks, the Jewish folk and the Confederate soldiers. And way over there,” he pointed with a long finger, “is what’s called Potter’s Field.”

“What’s Potter’s Field?”

“It’s where all the unmarked graves are.”

“Oh.”

I had just been to the cemetery a week ago, but my sense of direction wasn’t too keen. I squinted in the distance, looking for a grave with lots of fresh flowers. The cemetery wound around in several interlocking circles, and it was easy to get turned around. The road inside the cemetery was cobbled with red brick, and over the years, the ground had shifted so that the brick was broken and uneven with little green weeds growing in it. I tripped once on the bricks as I searched for Mama’s grave. Finally I found it.

I knelt down on the grass and let my knees touch the freshly turned soil. It was warm and moist from several days of rain. I reached in my jeans and pulled out a handful of dirt and sprinkled it over the grave. Mama loved the feel of the red Georgia clay in her hands. Sometimes before she started to paint in the back yard, she’d stoop down and wipe her hands in the dirt, bring some to her nose and smell. She said it got her in the mood for painting.

“I know you’re not here, Mama,” I whispered. “But I just thought it would be kind of fitting for your grave to have some of the clay from home. So I brought it to you.” The tears came.

Carl stood off at a distance as if he knew his place, and it wasn’t by me. Then I saw him walk down the hill towards another part of the cemetery. I cried for a while, and then I knelt down again beside the fresh dirt and smelled the thick scent of the flowers. All of them had wilted in the heat. I picked a white daisy from one of the bouquets and placed it on an open patch of dirt. “I miss you, Mama,” I whispered. Then I got up and brushed the dirt off my jeans.

“Thanks for bringing me, Carl.”

“It’s okay,” he said.

We were just outside the entrance to the cemetery when three white boys walked up to us. They looked about seventeen or eighteen, and were dressed as if they’d just gotten out from under some dilapidated car. One of them was staring at us with a sickly sort of grin on his face which made my stomach twitter inside. He was skinny and even taller than Carl, and his blond hair was cropped in a crew cut.

“My, my, my. What do we have here?” he said sarcastically, his cheeks bright red. “Ain’t this a sight to see. A white girl with a piece of black trash.”

Carl touched my arm, and we started walking faster, away from the boys. But they followed us.

“Hey there, boy! Don’t you ignore me when I’m talkin’ to you! What are you doin’ with this white girl? You aimin’ to hurt her or something?”

I wheeled around, heart pounding, furious, and said through clenched teeth, “It’s none of your business. Leave us alone!”

I saw then, out of the corner of my eye, that Carl looked terrified. That was the only word for it.

“You’re a feisty one, ain’t you, missy!” This came from the boy with a reddish-brown crew cut and a pudgy, smooth face. His T-shirt was soaked in sweat and his jeans hung low on his full belly. “Not afraid to hang around with trash, eh? Maybe that’s because you’re just white trash yourself.”

I stopped in my tracks, eyes flashing and hissed, “I’m not trash. You’re the trash! Now leave us alone.”

The sickly sweet smile on the first boy’s face disappeared, and he grabbed my arm, squeezing it until it hurt. He was skinny as a rail, but his hand gripped my arm almost fiercely. I tried to pull loose. Then I saw that the others were circling Carl like two hungry wolves. Carl looked at me and his wide eyes signaled me to be quiet.

“The colored boy knows when to be afraid,” the skinny boy said. He motioned to the others, the pudgy one and his friend who was shorter than the other two, wiry, with a head full of blond curls and greenish eyes and an evil sort of smile and a lot of muscles. They latched on to Carl savagely, just like wolves. I’m sure Carl could have beaten them both and gotten away if it hadn’t been for me. But I knew he wouldn’t leave me there.

They started hitting him in the face and the stomach while the skinny boy held me with my arms pinned behind my back. “Stop it!” I yelled. “Stop it!”

“Ain’t no one around to hear you, girly,” he whispered, obviously enjoying my mounting terror.

I bent my head down and bit him on the wrist as hard as I could. He cursed and swung his hand hard on my face. I went reeling and fell to the ground, hitting my head on the pavement.

“Hey, watch out, Richie!” the short, wiry boy yelled in between punches. “You wanna get us in trouble for foolin’ with a white girl?”

“She bit me! And anyway, I’ve got an idea. Knock the boy out. We’ll have a little fun with the girl and then leave her here and tell the police we found that colored boy aggressin’ her. They’ll hang him for sure.”

Carl groaned and I went numb, with my head throbbing and my cheek stinging. Richie dragged me behind a car and suddenly I knew what he had in mind. I kicked and screamed and bit until he took his hand and slapped me hard again, cursing. I fell back against the pavement. I thought if I acted like I’d been knocked out, maybe they’d leave me alone. So that’s what I did.

“You idiot,” the wiry boy screamed. “We gotta git outta here. Quick. Tell the police it was him, but let’s git!”

I lay perfectly still, forcing myself not to sob or heave or scream my guts out like I wanted to. Carl was about ten yards away, kind of crumpled up. I didn’t know if he was unconscious or dead.

But when the three boys were gone, he pulled himself to his knees and crawled over to me, heaving as he did. “Come on, Mary Swan,” he rasped. “We gotta get outta here quick. Real quick.”

His face was all bloody and swollen, and he was holding his side, but he managed to help me up. We limped out of the cemetery, both of us trembling as we scrambled down the street toward Mt. Carmel.

“You liked to git us killed, Mary Swan,” Carl panted. “Don’t ya know not to argue with rednecks, girl?”

“They were going to hurt you, and I was scared.” I looked up at him with one of my eyes shut. I could feel it beginning to swell.

He gave a weak chuckle. “If that’s how you act when you’re scared, I don’t wanna git around you when you’re feelin’ real mean!”

“You know what they were planning to do?”

“Yep. And I bet you they’re right now reporting somethin’ to the police.”

I don’t know if I felt more mad or more scared, but finally I said, “I’m sorry, Carl. It’s all my fault for wanting to see Mama’s grave. I didn’t realize it was so awful here. Has that ever happened to you before?”

“Happens all the time ‘round these parts.”

“You mean you’re used to it?”

He just nodded.

“But they could kill you!”

“Lotsa people git killed around here, Mary Swan. Either fighting over a girlfriend or trying to steal, or like with those boys—someone who just hates us because our skin is black. You learn to take a few punches, Mary Swan. If you fight back, those boys’ll come back with knifes and guns and a lotta friends.”

By this time, we’d reached the church and gone inside to the bathrooms. No one was around except for Ella Mae and Miss Abigail. With one look at us, they both came running.

“What in the world…”

“Some rednecks found us at the cemetery. Wanted to rough me up a bit, but Mary Swan wouldn’t let ‘em. She was determined to take all the brunt herself.” He tried to smile.

“My, my, chilin’” Ella Mae kept repeating as she and Miss Abigail got the first aid supplies and started cleaning our wounds. “I tol’ ya not go there, Mary Swan. Ain’t safe.” She grunted with disapproval. “Ain’t safe.”

I didn’t say anything, but kept looking at Carl and thinking about how he could have run off and gotten away. Left me with those white boys. But he didn’t. And I wanted more than ever to be his friend.

As I went to sleep that night, it was one of the first times I could remember when I wasn’t thinking about myself. I kept seeing that pudgy white face and Carl’s terrified black one, and I was thinking how comfortable I was cuddled in my bed and of how glad I was that Daddy hadn’t been around to see my bruised face when I had gotten home. If I wanted, I could close my eyes and forget about all the events of the afternoon. If I wanted, I didn’t ever have to go down to Mt. Carmel Church again.

But I was especially thinking that for Carl and Mike and James and poor little Puddin’ and probably everyone else who lived on that side of town, the fighting was just a way of life. They got used to it somehow and survived amid the violence. It was really my first peek at another reality, at something dark that made me shudder. Cruelty. I’d never really seen cruelty the way I had seen it that afternoon. I decided it would be so much easier to never go back to that part of town, to never be confronted with that part of life.

But of course, I wasn’t really the type to look for the easy way out. Like I’ve said before, I seemed to have a knack for stumbling into adventures. So as I fell asleep, thinking about Carl and Ella Mae and Miss Abigail and those three redneck boys, I kind of imagined myself as The Raven, not only of Wellington Prep School, but also as a big black bird that sat on a tombstone in Oakland Cemetery and warned the good people of the bad ones who were lurking somewhere just out of sight.

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog.

So simple, so straightforward. Every time I read this passage, the Spirit tugs at my heart and says, “Get the message? DON’T COMPARE! Don’t compare yourself with any other human; just follow me. Obey me. The course I have charted out for you is not like anyone else’s. If you are busy looking around at other people, you will soon grow restless, proud, jealous or angry. Just follow me.”

How are you “going out of your way” during this time of confinement and gradual reopening of life?

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog.

.

.ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog.

During the coronavirus pandemic, I’ve been deeply moved by so many random acts of kindness around the world, from a neighbor singing “Happy Birthday” to the 94-year-old who is home alone to John Krasinski throwing a prom for the class of 2020. So many different ways people are pitching in to help make this crazy time bearable.

And each Friday night, Andrew Lloyd Weber is offering 48 hours of free streaming for one of his musicals, starting at 8 p.m. (in France).

Well, we got in on it a little late, after he’d shown Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and Jesus Christ Superstar. But then we heard that Phantom of the Opera was coming on. Besides Les Miserables, Phantom is my favorite musical. Our sons grew up hearing that music playing loudly in the background (on a cassette tape, no less) while their stressed-out mom screamed high-pitched notes to match dear Christine.

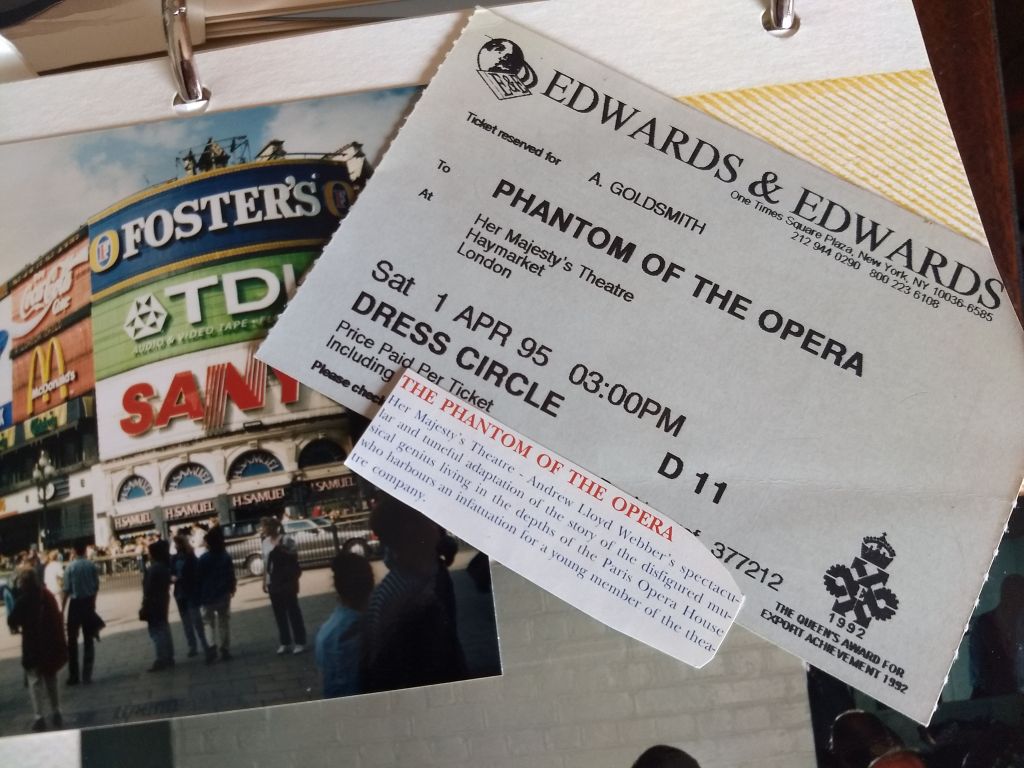

My first visit to The Phantom was with my beloved grandmother in 1995. We took a trip to England together to celebrate my first contract for my first novel and got to see The Phantom of the Opera in London.

It. Was. Perfect.

I’ve seen The Phantom at the Fox in Atlanta and watched The Phantom movie and listened to the soundtrack oodles and oodles of times.

But getting to watch the 25-Year-Anniversary production sounded like the best way to spend a Friday evening in confinement. So Paul and I tuned in at 8 p.m. on the dot. We enjoyed every minute and have been singing Phantom songs ever since, my high-pitched screaming mellowed into the evocative chords of All I Ask of You and Music of the Night.

So when Paul reminded me at dinner on the next Friday night that ALW (Andrew Lloyd Weber) was offering another free musical, I rushed in to watch it. It was called Love Never Dies. I should have taken the hint that if I had never heard of an ALW musical, there was probably a good reason for that. But I ignored that internal tug and blithely streamed it.

It. Was. Awful.

A sequel to The Phantom. A sequel???? What was ALW thinking? I hated the plot, in which he turned every single person in the play into a despicable character. I mean, poor Raoul, a drunk gambler, the Phantom having fathered Christine’s ten-year-old son in a night of passion—really, really?? Dear friend Meg freaking out and shooting Christine who dies in the Phantom’s arms as they’ve declared their love, and the Phantom supposedly keeping the boy who just found out the Phantom is his dad. And poor drunk Raoul is off to France.

The music had some nice songs, I guess, but mostly it was weird, Coney Island, freak-show bizarre.

And that’s when I thought, “Gracious, ALW! You should have quit while you were ahead! Don’t try to make a profit off of a sequel to a beloved musical (the most beloved in the world, if you believe the stats).”

I shook my head after finishing the show, and I did what I often do when I am really not pleased with a movie or book or musical. I see what others have said. And this was super interesting. There were bad reviews, all right. But it seemed like someone paid the top reviewers to simply NOT review it. As if, since reviewers, tail between their legs, were all embarrassed and unable to find one decent thing to say, many said nothing (or, ah-hem, were paid to say nothing. I mean this was ALW’s musical!)

So I want to learn that lesson again, Lord. If I’m trying too hard with a book, with a plot, if I’m turned down again and again, well, maybe I need to quit while I’m ahead. Leave that project behind and move on to something new.

You may redeem it later, as You’ve done with Two Destinies, the third book in my Secrets of the Cross trilogy. The first two novels, Two Crosses and Two Testaments, came out first in 1996 and 1997, while good ole Two Destinies waited 14 years to be published in the States. (Yes, it came out in Dutch, German, and Norwegian in the early 2000s, much to my delight.)

Fourteen years after it was written, TD made it’s American debut (and yes, it was a finalist for The Christy Award, thank you very much.) But I had to let that beloved novel go for a very long time.

I have another novel, The Wren’s Nest, that I wrote in 2015 that was published in Dutch, German, and Norwegian in 2016.

But The Wren’s Nest remains unpublished in the USA, having been turned down by many American publishers. I love the story and think it’s an important one. But maybe, just maybe, it isn’t the right story right now in America. Or maybe it never will be.

After several heart-breaking refusals by publishers, I laid it aside and concentrated on writing The Long Highway Home, When I Close My Eyes, and The Promised Land.

I don’t want to make the same mistake that ALW made with Love Never Dies.

Now I’ve decided to revisit the manuscript this coming year, do some heavy editing, and trust You, Lord, to show me if and when to publish it in the States.

Meanwhile, I’m immersed in research for a new novel and enjoying this process immensely.

May I pray, listen, write, and wait, all for Your glory, Lord.

And sometimes, may I simply quit while I’m ahead and trust You for the ‘if’ and ‘when’.

Is there anything in your life right now where the Lord is asking you to ‘quit while you’re ahead’?

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog.

Lord, my yard is shouting the proclamation that life wins! You win! You have won over death. You are alive. You have risen indeed!

And You will win over the Coronavirus.

Thank You for spring, Lord, and for a yard that shouts it so loudly. First the daffodils poked their heads out, and then they bloomed into bobbing bright yellow or white cylinders, while the forsythia shouted at me from beside the house and the driveway, “No, but look at me! Look how beautiful I am!”

And then the hyacinths bobbled their many fingered bodies in purple and pink splendor, with a fragrance that was oh so sweet. And then the tulips, yellow, red, and orange, started bragging, tall sentinels of beauty that eventually splayed themselves in individual worship, then closed up tight again at night.

Meanwhile, the cherry and pear trees were snowing petals and the ornamental cherry blushed with pink-kissed cheeks.

And then the calla lilies got in on the show, perfect Easter purity, all of them lifting their curled and gentle bodies to the sun.

Next my first bright pink rose peeked out, shockingly beautiful beside the calla lilies as its bush wound its way up the trellis on the side of the house.

Now my calla lilies are just bursting forth over and over and over again. Bragging!

And all the roses are beginning to bloom. The Peace Rosebush (as I’ve just learned her name) gave me five beautiful roses! Five, when she usually can only manage one. And other buds are almost, almost ready to bloom.

And my irises sprang up from underwater in the pond, waving flags of freedom and life while our goldfish gobbled up the food I tossed at them this morning.

It’s as if my yard is proclaiming victory over the virus—everything is more prolific this year. More daffodils, more tulips, more calla lilies, more blossoms on the trees, more roses, more breath-taking and sweet smelling lilacs.

More, more, more! You win, Jesus! You win over a virus that wreaks havoc. Life still wins.

Thank you, dear Lord, for spring’s victory in the midst of the devastation of the Coronavirus. May I win today by spending time with You and this yard and my husband and just enjoying the beauty of being the woman You love.

“For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation (including the Coronavirus) will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” Romans 8: 38-39

Are you convinced of this as well?

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog.

Lord, I keep hearing You tell me not to hurry.

Even in confinement, I’ve felt like I needed to get so much done, more even than usual. It started with finishing up edits for a novel and catching up on all the crazy correspondence after being offline for two weeks in early March. Then it morphed into not only the typical video calls we schedule with our One Collective workers and our families, but now, in confinement, we have calls with our church here in France and back home, with friends far and wide. With everyone. For which I am grateful, but I can sense an urge to hurry.

In the online Bible study I’m facilitating with other One Collective women, we’ve been discussing our tendencies to rush and hurry and of our desire to slow down in our minds even as we’re being forced to slow down physically during confinement.

Oh, You’ve slowed me down in my spirit so many times over the years. How thankful I am that ‘Sabbath’ and ‘rest’ and ‘solitude’ are familiar, welcomed words. But You know how often I need those reminders.

So yesterday in my daily devotions associated with the study, I was supposed to do a Lectio Divina from John 1: 35-39. Lectio Divina is a slow reading of the passage out loud several times, listening for a word or phrase that catches my attention. And then reflecting on it slowly.

But I’d just found out that the wonderful nursery down the street was open. I’d assumed it was closed during confinement, not considered ‘essential’. So I had never tried to go there. A month in confinement and no flowers to plant. But that hadn’t bothered me because of all of the perennial flowers bursting forth in the yard.

But suddenly I wanted to hurry through my Lectio so that I could get to the garden shop!

Ah, the irony!

Fortunately, You and the Lectio won out. Since I’d done a Lectio on John 1 several times, I decided to go back to my Proverbs reading, which I had paused for the past month while doing daily devotions for the Bible study. Next in order came Proverbs 19.

And Lord, it was again You showing up right here in the midst of my situation. You stopped me in my tracks in verse 2: “The one who acts hastily sins.”

Really, Lord, really? I’d been confessing the temptation to hurry through this Lectio, and then I read this.

Gulp.

I argued with You (not a good idea!) that I didn’t think hurry had to equal sin, but I sat with this verse anyway and thought about how often in the past I was begging You to free me from the old sins that can still trip me up. Yes, I confess them more quickly, yes, I spiral up, but how many times have I longed for You to completely uproot those idols.

But as I prayed and reflected, I thought to myself, “Hmm. Maybe You’re asking me to slow down in a different way. Maybe even before quickly confessing, (in a sense hurrying to get that yucky confession stuff over with), You’re asking me to stop, ponder, and wonder what’s Your invitation when I’m stirred by those old temptations. Maybe You want me to keep digging around in my soul so that You can heal any lingering junk that I notice.

Well, You weren’t finished with me in verse 2. A little further on I literally laughed out loud when I read: “…a poor person is separated from his friends…how much more do his friends keep their distance from him!”

Again Your Word and the words in Your Word, in this translation of Your Word, mystify, delight, and confound me!

First that word ‘hastily’ reinforced my thoughts about ‘hurry’, giving me plenty to ponder.

And then the words ‘separated’ and ‘keep their distance’ leapt out at me like flashing neon lights as we’re in our sixth week of social distancing, of being separated from our friends!

I felt like You were winking at me and saying, “Lizzie, how long has it been since you opened this Bible? Probably almost a month. Yes, you’re reading the Word, but not in this Bible. But dear, it isn’t hard for Me to speak to you with these words on the day you decide to open this Bible to the next chapter.”

Nothing is hard for You, Lord. I am constantly in awe, so please, please, let the awe and wonder and delight accompany me today and chase away the hurry, knowing that You are absolutely capable of getting me wherever You’d like me to be in my mind, body, and spirit. On time.

How are you slowing down in your mind, body, and spirit during this time?

P.S. I did spend a lovely morning (mask in place) buying flowers at the nursery after I finished my devotions! And yes, I soaked up that experience slowly!

ELIZABETH MUSSER writes ‘entertainment with a soul’ from her writing chalet—tool shed—outside Lyon, France. Find more about Elizabeth’s novels at www.elizabethmusser.com and on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and her blog.